|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Welcome to the May 2014 Newsletter from KAFS

The 26 people that have booked will have amazing memories to take home with them! The Study Days are proving extremely popular with the trip to view the Staffordshire Hoard fully booked, and Stonehenge has two places left with Roman Bath three. At home in July we are digging the last of three Bronze Age round barrows at Hollingbourne in Kent where last year in Barrow 2 we found a crouched burial and a complete bovine burial.

If you are not a member sign up soon or you may miss out on the experience of a lifetime, and please pass on to your friends! READING NOW

THE DEMON’S BLOOD

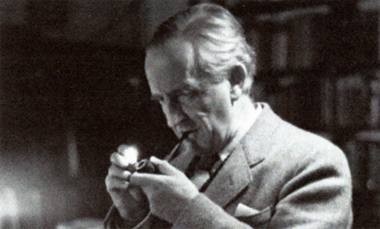

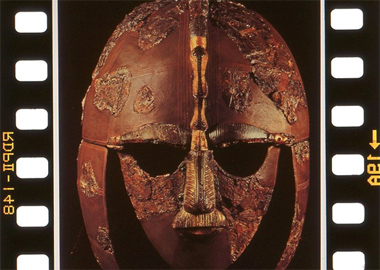

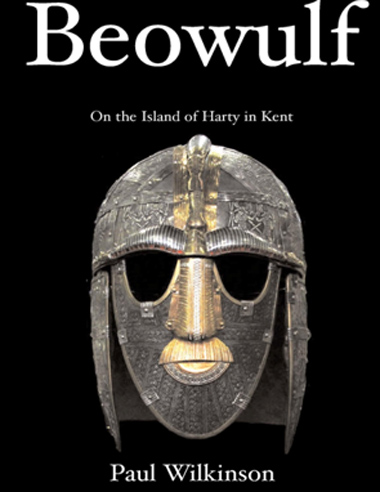

The Battle of Agincourt  Uffington White Horse Further back in time, this sceptical guide leads us into boundless realms of near-total ignorance. Some Palaeolithic images that appear to represent animals, women or the hypothetical earth goddess whom primitive peoples are supposed to have worshipped may be nothing more than natural lines in the rock. The Uffington White Horse might actually have been a cat or a dog. (Approached from the north-east, it looks like a prancing hen.) No one knows what it was made for. Like the I bronze age burial mounds that were copied by antiquarian Roman aristocrats, ancient sites such as Uffington, Silbury Hill, Avebury and Stonehenge probably became unfathomably mysterious within a few generations of their creation. As for the causewayed enclosures of southern England and the North Sea coast, the most we can say is that they were "special places into which people could go for special purposes at special times". Neo-druids who congregate anachronistically at prehistoric sites, turning them into gigantic car parks, may find Hutton's demystificatory approach sacrilegious. One of the austere pleasures of Pagan Britain lies in its frequent reminders that every age invents its own past, and that " it is impossible to determine with any precision the nature of the religious beliefs and rites of the prehistoric British". Does any sun-god worshipper visiting the Stonehenge campsite toilet ever spare a thought for Sterculinus, the god of manure? Even with sound archaeological evidence, Hutton argues, it is hard to distinguish ritual from practical behaviour. Did henges and hill forts serve a secular or a religious purpose, or is the distinction itself a modern invention? Apart from a few references to comparative studies of "traditional" or "tribal" peoples, Hutton does not try to formulate a definition. Instead, he picks his way carefully through the scholarship, politely pointing out the remnants of demolished theories and refusing to take sides: "It should perhaps be emphasised that no intervention in this debate is made here"; "Readers may choose whichever kind of explanation makes best sense to them, or pick and mix." The real subject of Pagan Britain – as Hutton says several times - is not the material evidence of ancient religion but the ways in which that evidence has been processed. Hutton writes as an even-handed observer of his own discipline, and it is here that most of the solid evidence of ritual behaviour can be found. Graham Robb Graham Robb’s most recent book is The Ancient Paths (Picador).  BEOWULF Translation by JRR Tolkien HarperCollins announced that a long-awaited JRR Tolkien (above) translation of Beowulf is to be published in May, along with his commentaries on the Old English epic and a story it inspired him to write. It is just the latest of a string of posthumous publications from the Oxford professor and Hobbit author, who died in 1973- edited by his son Christopher, now 89, it will doubtless be seen by some as an act of barrel-scraping. But Tolkien's expertise on Beowulf and his own literary powers give us every reason to take it seriously. Beowulf is the oldest-surviving epic poem in English, albeit a form of English few can read any more. Written down sometime between the eighth and 11th centuries - a point of ongoing debate - its 3,182 lines are preserved in a manuscript in the British Library, against all odds. Tolkien's academic work on it was second to none in its day, and his 1936 paper "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics" is still well worth reading, not only as an introduction to the poem, but also because it decisively changed the direction and emphasis of Beowulf scholarship. Up to that point it had been used as a quarry of linguistic, historical and archaeological detail, as it is thought to preserve the oral traditions passed down through generations by the Anglo-Saxon bards who sang in halls such as the one at Rendlesham in Suffolk, now argued to be the home of the king buried at Sutton Hoo. Beowulf, also gives a rich picture of life as lived by the warrior and royal classes in the Anglo-Saxon era in England in the period before the Angles, Saxons and Jutes arrived on these shores. And, on top of the story of Beowulf and his battles, it carries fragments of even older stories, now lost. But in order to study all these details, academics dismissed as childish nonsense the fantastical elements such as Grendel the monster of the fens, his even more monstrous mother and the dragon that fatally wounds him at the end. Likening the poem to a tower that watched the sea, and comparing its previous critics to demolition workers interested only in the raw stone, Tolkien pushed the monsters to the forefront. He argued that they represent the impermanence of human life, the mortal enemy that can strike at the heart of everything we hold dear, the force against which we need to muster all our strength - even if ultimately we may lose the fight. Without the monsters, the peculiarly northern courage of Beowulf and his men is meaningless. Tolkien, veteran of the Somme, knew that it was not. "Even today (despite the critics) you may find men not ignorant of tragic legend and history, who have heard of heroes and indeed seen them," he wrote in his lecture in the middle of the disenchanted 1930s. One of the best writers on Tolkien, Verlyn Flieger, identifies Beowulf as representing one of the two poles of Tolkien's imagination: the darker half, in which we all face eventual defeat - a complete contrast to the sudden joyous upturn of hope that he also expresses so superbly. In truth, it is his ability to move between the two attitudes that really lends him emotional power as a writer. His imaginative strength comes fundamentally from the way he engaged with ancient texts. He was fascinated by both what they said and what they left unsaid. It is no coincidence that his first version of The Silmarillion, the legendarium of Middle-earth, was called The Book of Lost Tales - because he purported to recreate through fiction the stories that survive only fragmentarily in the earliest writings of northern Europe. You can see how this works from an example from Beowulf.  At one point a poet tells how the "eorclanstanas" or precious jewels were carried "ofer ytha ful " , over the ocean's cup. Tolkien used the phrase "the ocean's cup" in the opening line of his very first Middle earth poem, written 100 years ago this September. The "eorclanstanas" inspired his Silmarils, the fateful jewels at the heart of The Silmarillion; and also gave him the name Arkenstone for the similar jewel in The Hobbit. The story is set within a gift-giving, cup-sharing scene that inspired the scene in The Lord of the Rings where Galadriel bids the Fellowship goodbye. Bilbo's theft of a cup from the hoard of the dragon Smaug in The Hobbit is indebted to Beowulf too.  The Anglo-Saxon helmet from Sutton Hoo Tolkien was often criticised by his academic colleagues for wasting time on fiction, even though that fiction has probably done more to popularise medieval literature than the work of 100 scholars. However, his failure to publish scholarship was not due to laziness nor entirely to other distractions. He was an extreme perfectionist who, as CS Lewis said, worked "like a coral insect", and his idea of what was acceptable for publication was several notches above what the most stringent publisher would demand. It will be fascinating to see how he exercised his literary, historical and linguistic expertise on the poem, and to compare it with more purely literary translations such as Seamus Heaney's as well as the academic ones. Tolkien bridged the gap between the two worlds astonishingly well. He was the archrevivalist of literary medievalism, who made it seem so relevant to the modern world. I can't wait to see his version of the first English epic. John Garth John Garth is the author of Tolkien and the Great War.  BEOWULF-On the Island of Harty in Kent Paul Wilkinson Amazon e-books Who would have thought it! Beowulf, that story from the very beginning of our time was always thought to have taken place in Denmark. But hey! In the 5th, 6th century during the time of Beowulf the Danes hadn’t got to Denmark, or the Jutes to Jutland, or the English to England! So what are the clues to where it, or even if it even took place. Well, luckily for us there are clues in Beowulf-but you will need to read the literal word for word translation with a good Anglo-Saxon dictionary at your elbow- rather than an interpretation of the poem by say Seamus Heaney. Beowulf, Hrothgar or even Wealhtheow don’t figure in history. So who does? Well the hero’s in the poem are told a story about an even earlier hero, someone called Hengest, and bingo we know all about Hengest from contemporary historians who tell us all about his adventures on the Island of Thanet. And next door to Thanet is another island now called Harty, but in the Domesday Book called Herte and in even earlier charters Heorot, and that is where the Beowulf story is set. The poem tells us Beowulf and his companions leave their homeland-the mouth of the Rhine and after two days sailing they see the ‘shining cliffs’- and their landfall was near Sheerness which means shining cliffs! They land at ‘Lands-End’ which you can see named on the map, and the ‘Warden’ picks his way down the cliffs to meet them- and on the same map you can see a small hamlet called ‘Warden’. Beowulf then marches inland on a ‘straet’ which is Anglo-Saxon for Roman road-of which Denmark has none. On arrival at the hall on Hearot they are greeted by Wealhtheow the queen of Heorot and her name means she is Romano-British (from Wealh) and theow means in an arranged marriage- the poem calls her ‘peace pledge between nations’! Beowulf is told about Grendal and his mother and Beowulf after killing both sails away. The topographic clues which surround Harty and indicate a connection with the epic saga Beowulf are not by chance. The barbarian war-bands that took over Kent were very particular over place-names, there are for instance over thirty five ways in Old English to describe a hill. Beowulf describes in great detail the voyage, (of two days), the ‘shining cliffs’, being met by the ‘warden’, the ‘paved road’ ascending upwards, the ‘tessellated’ floor, the Romano-British Queen, and the marsh surrounding Heorot inhabited by ‘supernatural beings’. All these are links in a story which would be recognised by its audience, maybe embroidered as good stories are, but in essence the truth, and recognised as such by contemporaries. The barbarians (or Saxons, as Roman writers called them) did not have an easy time of conquest. Nennius writes that Vortigern’s son Vortimer ‘three times shut them up [in Thanet] and besieged them, attacking, threatening and terrifying them.’ Vortimer fought at least four battles against Hengest and Horsa, the third battle was fought in the open country by the Inscribed Stone on the shore of the Gallic Sea (possibly Richborough). The barbarians were beaten and he was victorious. ‘They fled to their keels and were drowned as they clambered aboard them like women’ (Nennius, 43-44). At times like this is must have been reassuring to hear of sagas like Beowulf and remember the good times. And yet Hengest, Horsa, and Beowulf almost disappeared from written history. There is no direct line of genealogy from Hengest to the early Kings of Kent. It has often been said that this proves Hengest was a ‘founding myth’, and yet the truth could not be simpler, Hengest’s war-bands, and his grandson disappear into the maelstrom that was the siege of Mount Badon, a decisive victory for the Romano-British armies of western Britain led by Ambrosius Aurelianus. The battle was followed by a generation of peace and many barbarian war-bands returned to the continent. When the impetus of Saxon conquest re-started many years later it was with new kings who owed no genealogical allegiance to Beowulf, Hrothgar or even Hengest. And yet the sagas of Hengest and Beowulf survive, ‘it is written in a language that after many centuries has still essential kinship with our own, it was made in this land, and moves in our northern world beneath our northern sky, and for those who are native to that tongue and land, it must ever call with a profound appeal - until the dragon comes.’ (Tolkien, 1936: 36).  MUST SEE

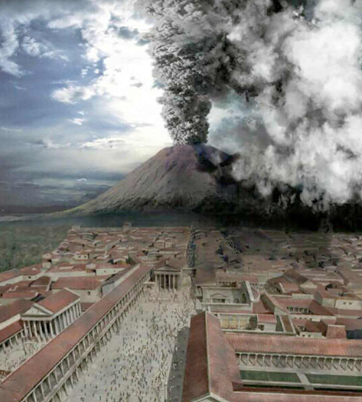

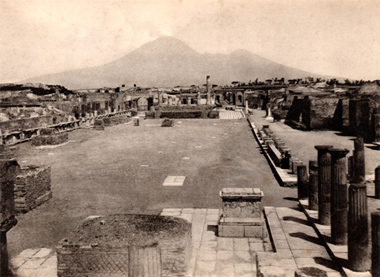

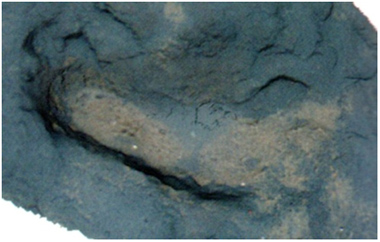

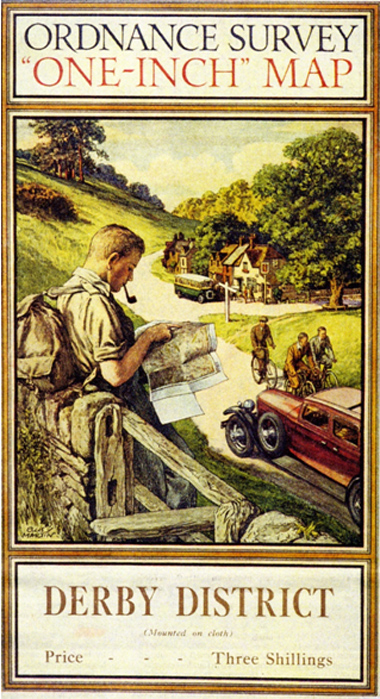

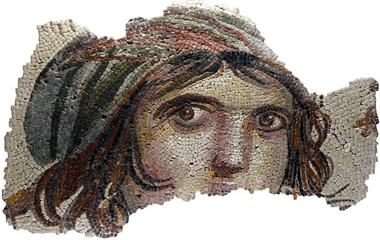

Stonehenge  To see this amazing site see details of the Kent Archaeological Field School Trip to Stonehenge on Friday 23rd May 2014 to witness the sunrise from inside the stones- the only difference there will be only a ten of us rather than thousands! Go to www.kafs.co.uk for information. Cinema: The Monument Men Sir Mortimer Wheeler, one of the fathers of modern archaeology, has been revealed as a hero of two world wars who almost single-handedly saved Roman ruins in Libya from the predations of Allied soldiers. A researcher working on his archive has also claimed that the man who founded Britain's first school for archaeologists was an unscrupulous "sex pest" who played down his first wife's crucial role in his achievements. The brigadier and television personality has emerged as a precursor to the "Monuments Men", US Army officers whose exploits in saving art treasures from Hitler were made into a film earlier this year starring George Clooney, Matt Damon and Hugh Bonneville. Joining Field Marshal Montgomery's North Africa campaign against Rommel in 1942, Sir Mortimer fought in the battle of EI Alamein and was horrified to see Allied forces vandalising Roman remains on the coast of Libya. Taking 48 hours' leave, he stormed across the country in a Jeep, posting cordons of military police around sites such as Sabratha and Leptis Magna, according to Gabriel Moshenska, lecturer in archaeology at University College London. Back in Westminster, outraged MPs were grilling ministers over reports' of Roman columns being tipped over by marauding Australians in Libya. As the Allies massed for an invasion of Sicily in July 1943, Sir Mortimer was so concerned about the fate of Italy's monuments that he wrote a pamphlet that was distributed to British soldiers under the title "Things Worth Saving and What to Do About Them".  "Remember the meaning which the Vandals, a Germanic tribe, gave to their name by their actions in this regard," he wrote. "History has a long memory." As a 28-year-old artillery officer in the final months of the Allied offensive on the Western Front in 1918, he led his men and 12 horses into no man's land to seize two German cannon at Butte de Warlencourt near the Somme. On his return to Britain in 1919 he took leading roles at the new National Museum of Wales and then at the London Museum, before founding the Archaeological Institute in London in 1934 with his wife, Tessa. Money was short, and the archives reveal that he resorted to several "scams" to raise funds. While the couple were working on Maiden Castle, the Iron Age hill fort in Dorset, Dr Moshenska said that Sir Mortimer sold hundreds of "slightly forged" ancient sling shots taken from nearby Chesil Beach. Tessa was tormented by his philandering. "He was, by all accounts, a bit of a groper and a sex pest and an incredible bully as well- and yet many of his members of staff were incredibly devoted to him.  In the 1950s and 60s he was one of first academic television personalities through BBC shows such as the (Animal, Vegetable or Mineral? -for which he was accused of preparing in advance. He was knighted in 1952, and died in 1976. Dr Moshenska said that Mortimer, for all his flaws, had been the first to open up archaeology to students, who were neither rich nor aristocratic. "It was part of the newly democratic society, part of encouraging this popular understanding of the past," he said. Oliver Moody Sir Mortimer Wheeler will feature in Voices of War: UCL in World War I, An exhibition opening next month at the college's Institute of Archaeology, Bloomsbury, central London. There will also be a lecture on the archives by J Moshenska and Katie Meheux as part of UCL's Festival of the Arts on May 28th at the Institute. Cinema:POMPEII 3D The CGI is impressive, but this disaster movie's terrible script makes it hard to go with the lava flow, says Kate Muir. Goodness gracious, great balls of fire! Pompeii 3D is a swords-and-sandals disaster epic that contains all the B-movie tropes you might hope for: slave-gladiators, evil Roman senators, totty in a toga, mounted romance, raining volcanic ash and seismic CGI. The only element missing is a decent script. Not that director Paul WS Anderson cares: sound and fury signifying nothing is his speciality, from the Resident Evil series to The Three Musketeers. That said, Anderson can choreograph a good sword fight, and his main man in the amphitheatre is the Celtic slave Milo, played by Kit Harington (Jon Snow in Game of Thrones). Harington is a buff fellow with a quilted six-pack but he lacks blockbuster leading-man gravitas beneath the sweat and stubble. Milo's story unfolds in AD79, beneath the grumbling belly of Mount Vesuvius — regular aerial views of the bubbling crater indicate a volcanic bout of indigestion and provide a plot during primary school history. Our Celt comes from a tribe of horsemen who are slaughtered by Romans, and Milo is dragged in chains from Britain to gladiate (1 hope that's the term). Milo is a tad resentful of the Roman who put his family to death: Senator Corvus, who turns up in Pompeii. The bullying senator is played by Kiefer Sutherland on lunatic thespian overdrive, with a "shurley shome and goes. His face is hamsterish, plus the bling rings on his gold breastplate indicate that he has raided Claire's Accessories down by the Forum. If, as a 24 addict, you've already wasted a week of your life with Sutherland, you know that Senator Jack Bauer/Corvus will be high on the ruthless spectrum. Just try to ignore the distant eruptions and puffs of ash as Corvus and Milo vie for the affections of the beautiful noblewomen Cassia played by Emily Browning, who is allowed two expressions: pouting and doe-eyed surprise. Since this movie is inaccurately rewriting history, why not perk up the totty-in-toga parts too? But Cassia sticks with the damsel in- distress tradition, hops on a horse behind Milo, and feels the earth move. Meanwhile, back in the amphitheatre, Milo is expected to enter into mortal combat with the African giant Atticus (Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje), but the dastardly senator has all the gladiators fight on long chains, like farmyard dogs. Axings, chain-decapitations, clubbing and double-handed sword fights erupt, which does take your mind off the possibility of a volcano dumping ash into the area at 15 million tonnes per second. The initial computer-generated effects are actually rather impressive, the flying 3D ash landing like dandruff in the cinema. The aerial views of Pompeii's coast look like a villa holiday brochure, and the fireworks from Vesuvius are magnificent, particularly the pyroclastic surges and the fireballs that crash like meteorites into the sea. Plus there's a tsunami moment that has a ship shooting up the main street. The problem is the eruption goes on and infinitum and beyond, while tiny humans continue their petty love-tiffs below. Fight has conquered the flight instinct, but we know from Pliny the Younger that the citizens of Pompeii were sprinting for the beaches and fields with "pillows tied upon their heads with napkins" as protection against flying debris. So why is Corvus settling scores and farting around in the amphitheatre on his chariot? Doesn't he know that if he stays in town he'll be turned into a toastie? The focus, though, is on Roman celebrity melodrama, rather than the 12,000 citizens who died, many preserved for ever in ash. And on that note, do enjoy the film's final shot, which might be the cheesiest and most predictable of the year.  Denise Allen of Andante Tours writes: My expectations weren’t high but I had to give it a chance – so I went to see how the real epic disaster story of Pompeii had been translated to big screen disaster movie. The posters in which the hero – a gladiator – stands in front of an erupting Vesuvius didn’t give me any comfort…red hot lava cascading down the slopes of the cone, for heaven’s sake, we KNOW there wasn’t any lava involved in the eruption of AD79. Casting all hope of historical and geological accuracy aside, I still wanted to see how they told the story. It began just as many historians and archaeologists have done, with an extract from the Pliny letters – where he describes the desperate cries of those at Misenum, some fearing death, others calling for it, many thinking the end of the world was nigh. There were also body casts on the screen, but not real ones (I could recognise most of those by now) – these were more like statues, but still, more than a nod towards the real evidence. The chronology and loose historical framework were right too – beginning with the campaigns in Britannia which pre-dated the eruption, linking individuals who fought there with those who later took power in Rome. Why our gladiator hero, who is the best fighter ever, was sent to provincial Pompeii to show off his skills rather than Rome is a bit of a mystery, but it’s fine as a dramatic device. They didn’t faithfully reproduce the plan of Pompeii for the digitally reconstructed city, but they had the stepping stones over the streets and other details quite accurately represented. It was interesting that the amphitheatre looked very like the real thing from the outside, with the transverse access stairs which are unique to the amphitheatre at Pompeii. I had been cross at the start of the film when a sweeping aerial shot gave us a view of the bubbling crater (‘but the crater was sealed!’) but now, instead of ash and lapilli, gigantic exploding fire bombs shot out of the crater. If it had really been like that there would be nothing left to visit! Pliny, it’s true, described the sea being sucked away from the shore leaving sea creatures stranded. But he made no mention of the giant tsunami which sent a trireme plunging along a Pompeii street. They did end with a pyroclastic surge, and it was worth waiting for – and the final scenes were a repetition of the opening, all the more poignant (some would say schmaltzy) for the engagement with the characters in the film. Denise Allen Cinema: Noah Kate Muir would rather swim for it than take a berth in Aronofsky's ark. The ambition of this damp, bloated biblical epic cannot be denied, but the director Darren Aronofsky's wacky take on Noah's Ark is likely to cause schism in the cinema foyer. Less a divisive Marmite movie than a Vegemite one, Noah stars the Antipodean Russell Crowe as a beardy, vegetarian environmentalist whose stewardship of the Earth gets extreme. Those who hoped for a cheery sing along moment — "The animals went in two by two, hurrah, hurrah!" — will find themselves trapped in an unforgiving rocky Icelandic landscape where everyone seems depressed. There are no swords and sandals, just sackcloth and volcanic ashes.  Russel Crowe looking more like Francis Pryor! Noah is in a foul, mercurial mood, suffering from Technicolor Garden of Eden hallucinations and garbled messages from "the Creator". ("God" is not mentioned.) "Did he speak to you?" asks Mrs Noah (Jennifer Connelly). "I think so," Noah says. "He's going to destroy the world." But not before Aronofsky destroys Genesis Chapters 6 to 9 by adding a geezer-nemesis in the form of Tubal-cain (Ray Winstone), giving Noah an adopted daughter, (Emma Watson) and bringing on rocket-propelled grenades and CGI giants. The Bible does say: "Giants (Nephilim) were on Earth in those days." It does not, however, specify "four-armed mega-Transformers made of crushed breeze blocks" that lumber around and then help Noah (played as a beardy, vegetarian environmentalist by Russell Crowe) wonders how everyone else had time to put on their cagoules to help Noah to build the ark, with unintentionally comic results. The CGI effects are Aronofsky's fall from grace: his talents lie more in avant-garde films such as Black Swan and Requiem for a Dream. The ark is the correct 300 cubits long, 50 wide and 30 high, but looks like a large shipping container. Aronofsky needs some Hobbity advice from Peter Jackson on battles and special effects — the Garden of Eden snake is bright green, pop-eyed and straight from a Fisher-Price toy catalogue. Yet the film also tries to explore — as with the ballerina in Black Swan and the searcher for eternal life in Aronofsky's The Fountain — the conflicted, obsessive side of its protagonist. The environmental message, as Man greedily destroys the Earth, will no doubt resonate all the way to the Somerset Levels, while one of the more fascinating adjuncts is the seven days of creation, a fast-forward Darwinian evolutionary zoom through time. This will not please Creationists and the drama has already enjoyed much religious controversy, with bans in Islamic countries for its depiction of a prophet and complaints from Americans that the portrayal of Noah is "too dark". But the makers have also been blessed by Pope Francis, and Crowe visited the Archbishop of Canterbury this week. Early on, in desperation, Paramount Pictures tried to add a Christian rock band over the credits. Aronofsky fought back and Patti Smith now sings the final song — and wrote a lullaby grunted by Russell Crowe in his worst Les Miserables mode. The rest of the score is high orchestral Hollywood provided by the Kronos Quartet. More thespian camp comes from Anthony Hopkins as the ancient, Welsh Methuselah, and from a Cockney Winstone as he stows away and starts snacking on the animals — causing the extinction of whole species. Two of Noah's sons are played by Logan Lerman as Ham and Douglas Booth as Shem, but the paterfamilias calls all the shots. Perhaps one of the Ten Commandments should be "Thou shalt not make an Old Testament epic". When someone brought Noah's Ark to the big screen in 1928 three extras drowned. This time, Aronofsky is merely out of his depth in blockbuster water-world. Kate Muir Celebrating Sutton Hoo 75 years on A new display of the British Museum's unparalleled Early Medieval collections (from AD 300-1100), including the famous Sutton Hoo treasure, will open in the new Sir Paul and Lady Ruddock Gallery (Room 41) on 27 March. Marking 75 years since the discovery of Sutton Hoo, finds from the ship burial in Suffolk, one of the most spectacular and important discoveries in British archaeology, will form the centrepiece of the new display. Excavated in 1939, on the eve of the Second World War, this 27-metre-long ship burial (below right) may have commemorated an Anglo- Saxon king who died in the early 7th century AD. It remains the richest intact burial to survive from Europe. Many of its incredible treasures, such as the helmet (right), gold buckle (below) and whetstone have become icons not only of the British Museum, but of the Early Medieval period as a whole. This project coincides with and relates to the Vikings: Life and Legend exhibition, which opened on 6 March at the British Museum in its new Sainsbury Exhibitions Gallery. The objects in Room 41 tell the story of a formative period in Europe's history. This time of great change witnessed the end of the Western Roman Empire, the evolution of the Byzantine Empire, migrations of people across the Continent and the emergence of Christianity and Islam as major religions. By the end of the period covered in the gallery, the precursors of many modern states had developed; Europe as we know it today was beginning to take shape. The new gallery gives an overview of the whole period, ranging across Europe and beyond - from the Atlantic Ocean to the Black Sea, from North Africa to Scandinavia. It is the unique chronological and geographical breadth of the British Museum's Early Medieval collections that makes such an approach possible. As well as giving the Sutton Hoo ship burial's treasures greater prominence within the museum, the new display will also act as a gateway into the diverse cultures featured in the rest of the gallery, in chronological, geographical and cultural zones. These include the Late Roman and Byzantine Empires, Celtic Britain and Ireland, migrating Germanic peoples, Northern and Eastern Europe, the Anglo- Saxons and the Vikings.  Among the outstanding treasures on display will be the Lycurgus Cup, the Projecta Casket, the Kells Crozier, the Domagnano Treasure, the Cuerdale Hoard and the Fuller Brooch. The design, object selection and interpretation aims to develop a more coherent narrative and to display star objects more effectively than ever before - this includes extraordinary objects from a period that was anything but the 'Dark Ages'. The new display will also feature artefacts never shown before - including Late Roman mosaics, a huge copper alloy necklace from the Baltic Sea region, and a gilded mount discovered by X-ray in a lump of organic material from a Viking woman's grave, over a century after it was acquired. Despite so many different peoples spread across vast distances over a long period, the key themes running through the gallery's narrative will put the objects on display in context, highlighting how diverse parts of the collections relate to one another. Lindsay Fulcher To visit the Galleries this September with the Curator on a private KAFS visit which will include handling the Faversham treasures-kept in boxes in the basement register your interest on [email protected]  • Masterpieces: Early Medieval Art by Sonia Marzinzik (published in hardback by British Museum Press at £25) explores the history of Europe and the Mediterranean from the end of the Roman Empire to the 12th century, as told through objects in the British Museum's vast collection. British Museum WC1 020-7323-8299 Exhibition: The Magic of Mosaic A magnificent 3rd century mosaic from the city of Lod in Israel goes on show at Waddesdon Manor in Buckinghamshire in June. It was divided into sections in order to make it easier both to lift and to transport. It has since been displayed in a number of international institutions in the USA and Europe. The city of Lod, known throughout most of antiquity as Lydda, was an important centre for industry and scholarly activity in the region, and its inhabitants were predominantly Jewish from the 5th century BC onwards. It was destroyed in AD 66 by the Romans at the beginning of the First Jewish-Roman War and later rebuilt as a colony, renamed Diospolis ('City of Zeus'). It is said to be the birthplace and resting place of St George, who was reputedly buried there in AD 303, around the time of the mosaic's production. By the middle of the 4th century the majority of its inhabitants had become Christian. The city remained under Roman control until the Arab conquest in AD 636. As the city has been continuously occupied, there has been limited archaeological activity, which makes the discovery of the Lod Mosaic and the implications of what else may exist of the Roman city all the more intriguing. This mosaic is one of the largest, best-preserved examples of Roman mosaic work in the whole Levant region. While a pattern-book was probably used for some of the standard design features, the mosaic's subject matter is in itself fascinating. What is depicted is an array of wild and domestic animals along with a marine scene, but no deities or people - the only indications of human life are two merchant ships and a basket of fish.  This is highly unusual and adds to the mystery of the owner's identity and nationality. All that is certain is that only a wealthy person could have owned such a beautiful floor. While there is a lack of clear religious symbolism, a number of motifs that are open to interpretation can be attributed to Jewish, Christian and pagan traditions. For example, the lions in the central panel could be seen to represent the tribe of Judah, whose symbol was the Lion of Judah. However, the same iconography was also used by Christians for Jesus, who is described as such in the Book of Revelation 5:5. As for pagan symbols, the trident, which is the symbol of Poseidon, is depicted between two dolphins in the four corners of the central panel. Meanwhile the inclusion of a ketos (sea monster), between the mountains (possibly representing the mountains of Ethiopia) in the central octagon, makes a reference to Classical mythology. It brings to mind the myth of Perseus and Andromeda, in which the hero saves her from a sea monster. In general, though, the overlapping and varied possible symbolism is open to interpretation, and many motifs would just have been standard designs, so it is impossible to draw any firm conclusions about the owner's religion from the design of the mosaic alone.  The diversity of the animals depicted is impressive, with the central octagon containing a rhinoceros, giraffe, tiger, bull, elephant and two lions, as well as the ketos. The elephant, rhinoceros and giraffe were unfamiliar to residents of Lod and would have seemed very exotic - rhinos and giraffes rarely appear in ancient art. Yet despite this apparent lack of knowledge, the detail of the animals is astonishing, from the cross-hatching on the elephant to represent its wrinkled skin, to the distinctive markings of the giraffe and tiger. While the portrayal of the rhinoceros and the bull :is not very lifelike, the multi-tonal shading on all the creatures shows that an extremely sophisticated artist was at work here. There has clearly been great attention to detail, evident particularly in the elaborate plumage of a peacock. Astrid Johansen Predators and Prey: A Roman Mosaic from Lod, Israel will be on show in the Coach Houise of the Stables at Waddesdon Manor from 5th June to 2nd November 2014 (www.waddesdon.org) BREAKING NEWS: Footprints from the Past For three weeks last summer a series of strange indentations appeared in rocks on the beach in Happisburgh, Norfolk, before they were rubbed out by the surf.

Had archaeologists not been on hand to record them, it would have been a lot easier for historians.  Professor Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum said that the footprints, which can be dated by their position in the layers of sediment, may be up to a million years old. The prints show the path taken by at least five individuals including an adult male and three children, who appeared to be "pottering along" a river estuary, heading south. Archaeologists from the British Museum and the Natural History Museum, where images of the discovery will go on display next week as part of Britain: One Million Years of the Human Story,said that they had been baffled at first. Mick Ashton, a curator at the British Museum, said that the prints appeared suddenly when a protective layer of sand was stripped away by thesea. "We scratched our heads a bit," Dr Ashton said. "It was only after recording them for a few days that we realised their importance." A colour diagram showing detailed measurements of the depths of the prints shows not only the outlines of the feet but the shape of their arches, heels and in one case the imprint of four toes. Referring to Norfolk's reputation as the butt of jokes about in-breeding, he said: "I promised my colleagues that I wouldn't mention Norfolk in the same sentence as the four toes." The largest of the prints, the equivalent of a British size eight shoe, is thought to have belonged to a male hominid of the species homo antecessor (pioneer man), which was succeeded by two other human species before homo sapiens. This individual was about 5ft 8in, larger than any female of the species, which has also been found in Spain. Dr Ashton said the creatures had smaller heads than our species, but were evidently hardier because although summer conditions were similar to today's weather, winters were more like those in southern Scandinavia. The river where the footprints were made was probably an early course for what would become the Thames, which moved southwards over the millennia. An archaeological dig 180m along the beach has uncovered prehistoric tools and animal bones that suggest that the family might have eaten deer, horse and bison in an area where mammoths, hippopotamuses and rhinoceroses also grazed in the valleys. Professor Stringer said that the footprints push back the evidence of when humans first inhabited Britain. "Rather than having a continuous occupation of Britain, which people would have argued ten or twenty years ago, we think that there could have been ten occupations of Britain. We're now in the tenth occupation, which we hope will last a long time." Isabelle de Groote, an expert in ancient human fossil remains at Liverpool John Moores University, said that the presence of children's footprints suggested that this was not a hunting expedition. "They seem to be following the river, but there's some pottering around going on. "If you think of going for .a walk on the beach, yes, you walk in a line, but the kids run around." Roger Bland, the keeper of the British Museum's department of prehistory, said: "They look to me like they're having a party." Jack Malvern A one day conference Britain: One Million Years of the Human Story with lectures by Chris Stringer, Nick Ashton, and Simon Parfitt will be held on 31st May. Tickets cost £35 to book see www.nhmshop.co.uk/tickets/conference  WAVE GOODBYE Ordnance Survey paper maps I was first taught to read a map when I was around 11 years old. My stepfather shook out the Ordnance Survey OL 30 Explorer map (Yorkshire Dales - Northern & Central Area) over the kitchen table in our holiday cottage: a paper tablecloth of sandy yellow and duck-egg blue, whorled with orange skins. The map's text resembled a fantasy language: Oliver High Lathe, Gollinglith Fleet, Grouse Butts, Washfold Wham, Sprs, Resr (dis), Flaystones, Batty Nick, Acoras Scar, Shake Holes, Horse Helks, Three Holes Stoop (BS). Some of its symbols were relatively straightforward to decipher, such as a miniature telephone handset, teepee or blue fish. But others - like the menu of subtly differentiated dotted lines, or randomly placed numbers in varying fonts, colours and angles - made no sense to me. Leaning over the map, my stepfather began sifting names I recognised. He ran his thumb along familiar paths and identified faraway landmarks my parents had pointed out during walks. He deciphered a line of green diamonds as a "National Trail/Long Distance Route" and distinguished it from a chain of black pinpricks (Boundary: Civil Parish (CP)) or tiny segregated dashes (Electricity Transmission Line). He encouraged me to imagine myself, a tiny speck, crawling over the paper landscape. He explained that the tighter the orange contour lines were bunched, the heavier I'd feel as I made my way across them; and that at points where the path disappeared, I could find my place on the map by attending to details I'd never before noticed: the coalescence of field boundaries, or a shift from "Bracken, heath or rough grassland" into "Scrub". He taught me how to line up the compass's red triangle at 0°, to lay it along the map's grid in the direction of north, to identify a landmark and navigate a path towards it. A small blue triangle on the map was a "trig point" and generally promised a good view, he assured me. A miniature pint glass meant a much-deserved rest. That first lesson in map reading irrevocably changed my idea of that glorious Nidderdale landscape; of all subsequent landscapes. Until I learned to map read, I had been hiking as if in a tunnel, flanked by dry-stone walls, blindly stumbling after my parents. Visible landmarks had passed on either side, as pleasantly unremarkable as sheep or daffodils. I had been rooted to ground level, eyes trained on the immediate vicinity. But the map broke down the walls of my tunnel vision, swept the ground from beneath my feet and launched me high in the air, elevating my mind's eye to a perch beside the bird's-eye viewpoint of the OS map. On that map, the world was laid out all before me; a carpet of fields, moors and possibilities. It's no coincidence, I think, that the earliest accounts of human flight compare the view of the landscape beneath to a map. Because it works both ways: hovering over a map is like flying. Twenty-three years later, I'm still a confirmed map addict. I still visualise making my way through the world as a tiny speck, crawling across a map. If you ask me for directions, I'd much rather sketch you a map on the back of an envelope than recite an itinerary of right and left turns. Before a long run, I squirrel away in my memory details from the OS map in my backpack; emergency provisions for the imagination that will fuel unanticipated detours from my planned route and return me safely home. The freedom that maps bestow to wander at leisure across the nation has granted Ordnance Survey's maps in particular an affectionate place in the hearts of map readers across centuries. The abundance of bird's-eye views in poetry, fiction and art testifies to a creative, active, imaginative relationship between the map-reader and their charts. These types of maps have appeared in literature as assertions of land ownership, patriotism and colonialism: Lear's "division of the kingdom" is executed on a map, and Heart ofDarkness's Mario entertains a "passion for maps", particularly a "large shining map [of Africa], marked with all the colours of a rainbow".  Even in a satnav world, the tactility of paper maps punctuates modern poetry. Moniza Alvi depicts a woman "rub[bing] her face against a map of the world" or "rollfing] like a map", Matthew Francis writes affectionately of "a mud-spattered map already separated by too much folding into its nine panels". Paul Muldoon's "The Old Country" is nostalgic for a time when "Every glove compartment held a manual and a map of the roads, major and minor". The conventions and aesthetics of paper maps also inspire imaginative responses, from poetry (Nigel Forde's "Conventional Signs" laments the failure of OS map symbols to convey the individual character of places). In comparison, satnavs seem to inspire few literary devotees beyond authors of humorous poems comparing their didactic nature to wives and back-seat drivers. In The Wild Places, Robert Macfarlane is scathing about the constrained viewpoint captured in road maps, writing that " it encourages us to imagine the land itself only as a context for motorised travel... The road atlas makes it easy to forget the physical presence of terrain, that the countries we call England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales comprise more than 5,000 islands, 500 mountains and 300 rivers." Arguably Daniel Defoe's linear routes around portions of Britain i n his 1720s Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain were literary equivalents of contemporary road maps, but they were ultimately designed to be pieced together into a panoramic overview of the newly formed nation. A satnav does the navigational graft for you. Maps coax their readers into doing the lion's share of the work, They require an act o f code-breaking to distinguish the symbols for railway embankments from gravel pits; club houses from cattle-grids; coppice from saltings. They demand close attention to variations in the landscape and navigational initiative. But, as sales of paper maps decline year-on-year, and usage o f digital apps and devices rises, there is a sea change taking place in the way we consume and use geographical information. Could this mark the end of the map, and if so, should we be worried? Evidence for the waning popularity of the paper map is clearly visible in sales figures provided by Ordnance Survey, Britain's national mapping agency. OS has been synonymous with paper maps since the publication of its first map, in 1801, of Kent: a military survey designed to assist Britain's defensive efforts against revolutionary France. The stunning covers designed by Ellis Martin for the one-inch-to-the mile Popular Edition in the interwar period secured for Ordnance Survey's folded maps an iconic status among hikers and cyclists, and today OS accounts for 95% of the share of the UK paper map sector. But, although the deterioration of sales of OS paper maps is slower than that experienced by its rivals, the organisation has nevertheless reported a 5% year-on-year decline in purchases of its staple Explorer and Landranger series of folded maps. The 2004 framework document that sets out Ordnance Survey's future priorities unequivocally stipulates that the organisation's chief responsibility (the source of 93% of its revenue) is to maintain and improve its massive geospatial database, the OS Master Map. Beside this gargantuan task, the much loved paper maps, and the leisure market that craves them, risk looking like a sideline. The Master Map is primarily used to license different types of digital information to the private and state sector, such as a recent project to supply data necessary to underpin a centralised record of road works in Scotland. And it is a jaw dropping achievement: updated up to 10,000 times a day, the Master Map is the most up-to-date, comprehensive and detailed bank of national geographical information owned by any country on Earth. Indeed, some feel that the database's driving commitment to "up-to-dateness" is or mobile phone: it won't run out of batteries or lose signal at the top of a mountain, just as the clouds close in. It should come as no surprise that the OS paper map refuses to die without a fight - it has been exciting loyalty and love among its users since its earliest days. Despite OS being established as a military survey in 1791, its first real director - a visionary called William Mudge - foresaw the possibilities that a complete, accurate national map might offer the general public. In all its applications, from improved scientific knowledge of the Earth to furthering the progress of the incipient industrial revolution, he predicted that it would be "the Honour of the Nation". Mudge successfully proposed selling maps to the public (albeit at prohibitive cost), and oversaw the publication of accounts of his mapmakers' endeavours, priced to reach an audience far wider than military engineers or geographical scientists. The French revolutionary and Napoleonic wars placed a premium on up-to-date, detailed geographical knowledge of Britain's borders. When his superiors sought to classify such information, Mudge fought hard – but unsuccessfully - for continued public access to the maps. But the 19th century saw Ordnance Survey's readership expand, as the price of its maps steadily decreased and the number of licensed retailers rose. By 1848 OS maps were no longer the preserve of "gentlemen [who wanted] to procure a map of the country surrounding their own habitations" for proud display, as an 1818 advert had suggested, but were placed, in the words of the Daily News, "within the reach of all who may require such aid". OS maps had not been formally linked to the cult of landscape that dominated the literary and leisure culture of their earliest years: after all, who folds a £100 map into their pocket or exposes it to the British weather? That association was cemented later, during the interwar period that saw the introduction of a new, stylish, affordable series of folded one-inch tourist maps to exploit the extraordinary explosion of enthusiasm for hiking, cycling and immersion in the British outdoors. John Betjeman recalled at odds with the ethos of paper maps. Rapid changes affecting areas of the British Isles mean that many maps are out of date by the time they reach bookshops' shelves. Most of the Explorer and Landranger series are only updated every two to five years. So to combat the paper map's inbuilt tendency to obsolescence, Ordnance Survey has been developing apps to equip hikers and cyclists with the most recent digital geographical information. Some (such as OS Map Finder and OS Ride) could entirely replace paper maps, but others (such as OS Locate, which provides users with National Grid References for their location) are designed to act as companions. However, the organisation is acutely "aware of the fact that customers love [paper maps]" and of the "passion and iconic image" they produce, Robert Andrews, head of corporate communications at OS, assures me, and recent media reports that some of the OS's Explorer and Landranger series will soon be available only on a "print on- demand" basis turn out to be unfounded. "Maintaining a national series of [paper] maps" remains a firm statutory commitment of Ordnance Survey, Andrews promises. And he dismisses suggestions that the organisation's duty to continue printing these maps might be contrary to its commitment to the database. Instead he points out that the two actually exist hand-in-hand. Even the OS's decision in 2010 to outsource the printing and warehousing to private firms doesn't really seem to indicate an abdication of responsibilty for the artefacts themselves. (Ordnance Survey's history has been punctuated by similar outsourcing of its maps' publication: even its first map was printed not by OS's military headquarters but by William Faden, royal geographer to King George II.) It is true that all Ordnance Survey's leisure products combined – paper maps and their modern-day heirs, mobile phone apps - are now only responsible for 7% of the organisation's overall revenue. But within that sector, paper maps continue to be the OS's most popular product: 1.9m were sold last year, compared to around 200,000 downloads of their digital equivalent. Even at a technological level, a paper map has a clear advantage over a satnav of representation - known as "traverse surveying" - undoubtedly has an important function, usually in purposeful navigation, when getting from A to B as fast as possible is the priority. And then there is the bird's-eye view. A vision of landscape drawn from an elevated viewpoint, this produces what the poet James Thomson called "an equal wide survey" of a territory. Its image is emphatically non-linear, sprawling to the edges o f the paper on which it is drawn. It doesn't reveal everything about a landscape – Jorge Luis Borges wrote of the absurdity of the intention to make a map on the scale of 1:1 - but its information is typically various, detailed, seemingly impartial. Its vocabulary of symbols is often obscure, and to read it requires active interpretative exertion - but this effort is repaid with the freedom to choose one's own route, and a far greater emotional connection between the map-reader, the map and the landscape. If the traverse survey mimics the viewpoint of the driver whose eyes are focused on the road ahead, then the bird's-eye view is the leisurely, expansive, panoramic gaze of the hiker, looking down from the top of a mountain. These two very different forms inspire similarly different methods of engagement from their users. But both types of maps have their place, of course. Traverse surveys dominate the market in digital consumer navigation, particularly satnavs and other handheld devices, whose small screens are ideally suited to the swift display of pared down information. And I 'm grateful for these gadgets when I'm driving, or running purely for speed. But they encourage passivity. They keep us in ignorance of a world beyond the immediate vicinity. They suppress diversions from the fastest route. They quash active attempts to immerse ourselves, knee-deep in the bogs and fescue grass of the British countryside. William Wordsworth wrote of "dreaming o'er the map": does anyone dream over a satnav? The end of the map is a decline in active engagement with our environment. Emotionally, physically, imaginatively: we will be poorer for it. Rachel Hewitt Rachel Hewitt's Map of a Nation: A Biography of the Ordnance Survey is published by Granta. STUDY DAYS A day in Bath followed by a Twilight Tour & Dinner in the Roman Baths. KAFS Visit on Saturday 13th December at 9.30am with Stephen Clews Curator of the Roman Baths. 9.30 Introductory talk by Stephen Clews 10.45 Visit to the Pump Room for spa water 11.15 Visit the Roman Baths site, including special access to underground passages not open to the public. 12.30-1.30 Lunch break 1.30 Tour of old spa buildings and Bath's Georgian upper town 4.30 Meet your evening guide at the Great Bath for an exclusive guided tour around the torch lit baths followed by a three course dinner at the Roman Baths Kitchen. A day in the beautiful Cotswolds and the graceful city of Bath will reveal the Roman heritage of the area. Our tour leader will be Stephen Clews, Curator of The Roman Baths for the last 16 years, and prior to that Assistant Curator at the Corinium Museum in Cirencester. The study day begins with an introductory talk by Stephen Clews followed by a gulp of spring water in the Great Pump Room at Bath. Then we visit the Roman Baths and Temple complex built around the hot springs of Bath, which became a place of pilgrimage in the Roman period. This tour will include special access to underground passages and the spa water borehole. The spa theme will continue as we trace the story of seven thousand years of human activity around the hot springs, which has created this World Heritage city. The afternoon will conclude with a walk around the Georgian upper town. In the early evening we meet up at the Roman Baths for a torch lit guided tour of the Roman Bath Museum followed by Dinner at the Roman Baths Kitchen opposite the entrance to the Roman Baths. To join the ‘behind the scenes’ visit with KAFS on Saturday 13th December 2014 email your booking to [email protected] Places available for five members only at £75 per person. FIELD TRIPS Join KAFS on a field trip on 26th-28th September 2014 to Zeugma. It is a not a trip for the light-hearted but there are direct flights by Turkish Airlines direct to Gaziantep from Gatwick at about £250 return. Local accommodation and a local mini-bus plus local guide will be available and Dr Paul Wilkinson will be your guide. We have nine places left, mini-bus and museum costs to be shared amongst members. For more details email Paul Wilkinson [email protected]  The ancient city of Zeugma was originally founded as a Greek settlement by Seleucus I Nicator, one of the generals of Alexander, in 300 BC. King Seleucus almost certainly named the city Seleucia after himself; whether this city is, or can be, the city known as Seleucia on the Euphrates.  In 64 BC Zeugma was conquered and ruled by the Roman Empire and with this shift the name of the city was changed into Zeugma, meaning "bridge-passage" or "bridge of boats". During Roman rule, the city became one of the attractions in the region, due to its commercial potential originating from its geo-strategic location because the city was on the Silk Road connecting Antioch to China with a quay or pontoon bridge across the river Euphrates which was the border with the Persian Empire until the late 2nd century. Museums we will visit include: • Archaeological Museum This local archaeological museum hosts some stunning mosaics excavated from the nearby Roman site of Zeugma. The museum, which also has a small cafe inside, is wheelchair accessible. • The Castle's Museum. It is a great opportunity to learn from the Turkish point of view what happened in the WWI, especially what concerns to the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and the further occupation. The view from the top of the castle is amazing. • Kitchen Museum. Museum about Turkish traditional cuisine, food, ingredients, tools and bon tòn. Very interesting. • Zeugma Mosaic Museum. Zeugma Mosaic Museum, in the town of Gaziantep, Turkey, is the biggest mosaic museum on the world, containing 1700m2 of mosaics. For more information on Zeugma see: www.zeugmaweb.com/zeugma/english/engindex.htm QUIZ The first reader to identify this crop mark and its location wins a free weekend of their choice at the Kent Archaeological Field School. Send your answers to [email protected]  SHORT STORY "If history were taught in the form of stories, it would never be forgotten" Rudyard Kipling Faction articles of life in Roman Kent by Paul Wilkinson have been published monthly in the county newspaper of Kent and are a hit with readers. For the amusement of academics read on! Some years ago we were field walking as part of an archaeological survey just to the west of Faversham in a remote field on what had once been an island overlooking the Swale Estuary. The field was littered with the remains of a Roman building, but in one area the Roman building material was dense and mixed with very fine decorated Roman pottery. We returned to the field many years later and proceeded to excavate the structure which as it was revealed left us all puzzled, then suddenly it came to me- it was an octagonal building, and I knew instantly that it was very special indeed. No other Roman building of this type had been found in south-east Britain, and there was only two known from the rest of Roman Britain. I also knew what the function of this building was- it was a Christian baptistery from the time when the Roman Empire changed its state religion from the old pagan gods to Christianity.  Weeks later we had uncovered the most exciting Roman building ever to be found in Kent. The architecture was so sophisticated, an octagonal ring of stone walls and an inner ring of arcaded stone walls and at each of the of the eight corners a radiating stone buttress to hold up an inner tower, itself with upper windows which would have streamed light down on to the central plunge pool fed by its own aqueduct. Attached to the octagon were two furnace rooms and a large changing room or narthex. The rest of the building including the room with an apse was a Roman bath house dating from the time of Constantine, the first Christian Roman Emperor who was proclaimed as such in Britain.But why an octagon shape? In Christian symbolism the number eight represents eternity and rebirth, because the world was created in seven days with life starting on the eighth day and Christ rose from the dead on the eighth day. For early Christians eight was the number which symbolised the resurrection of Christ and the formation of the New Covenant. The octagonal plan survives at the baptistery at Grado (c. 450) and at Frejus and Albenga. In some baptistery’s the octagonal core expands in niches projecting outwards as at Nocera, or surrounded by ambulatory rooms, square at Aquileia (c. 450), Riva San Vitale (c. 500) and octagonal in the Baptistery of the Arians at Ravenna (c. 480). I knew the history of these buildings and on the last day of excavation I sat on the edge of the plunge pool pondering and sweeping the dust with my hand when I uncovered a large coin, I picked it up and blew the dust away and as I did I saw the engraving of a Jewish Menorah appear, I heard a sound and looked up and there was a man smiling at me and holding out his right hand. He said, ‘thank goodness, we were looking for that’. I looked around and my world had been transformed- the walls were up, a blinding light from the windows in the tower were streaming down on to the plunge pool making it dance and sparkle in the sunlight, All around me I could hear the sound of cascading water and music, and it was so hot. I looked back at the man and asked why did he need the coin? Attalus explained that today was the baptism of his first born son into the Jewish faith and the tradition was to buy back the child from the priests with five coins engraved with a five-branched Menorah-‘and I only have four coins, but come let me show you around’. We walked through the bath house admiring the decoration and Attalus explained that for most of the time the building functioned as a bath house but once a month on a Sunday Christians used it to baptise new followers, ‘total immersion you know’, Attalus said laughing. We got to the main entrance and Attalus unlocked the main door. ‘Look, I have to go’, and we said our goodbyes. I looked out the door towards the Swale and turned round to find the building once again a ruin with the dust of history blowing in the wind. I looked down and laying there was the key to the door dropped by Attalus, I picked it up and smiling walked to join the rest of my companions. The full archaeological report of Bax Farm can be found on www.kafs.co.uk Paul Wilkinson COURSES KAFS Courses for the rest of 2014

KAFS BOOKING FORM You can download the KAFS booking form for all of our forthcoming courses directly from our website, or by clicking here KAFS MEMBERSHIP FORM You can download the KAFS membership form directly from our website, or by clicking here |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If you would like to be removed from the KAFS mailing list please do so by |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||